Blog

The Chimera of Private Finance for Development

A fashionable idea has yet to fulfil its promise

Ten years ago world leaders agreed on 17 sustainable development goals (sdgs), from ending hunger to ensuring decent work for all. An ensuing conference in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, had the harder task of working out how to pay for them. The World Bank and other multilateral lenders talked of turning “billions to trillions”. One idea was that small dollops of public money could spur much larger flows of private capital. The pensions and insurance premiums of the rich would build roads and power plants for the poor.

A follow-up conference will begin in Seville next month in a glum mood. Public finance for development is in crisis. Almost every big bilateral donor is cutting aid. Government spending is falling in two-thirds of African countries as they grapple with debt. More than ever, they will pursue private finance to fill the gaps. But so far they have been on a wild-goose chase. Billions have not become trillions, however you choose to measure it.

The slogan was “well-meaning but silly”, says Philippe Valahu of the Private Infrastructure Development Group, which funds projects in developing countries. Its silliness is most obvious in Africa. The idea was always angled at places with middling incomes, and many African countries are still quite poor. But Africa is also where needs are greatest. The familiar cycle of grand promises and modest delivery is seen by Africans as “a betrayal of trust”, says Daouda Sembene, a former presidential adviser in Senegal.

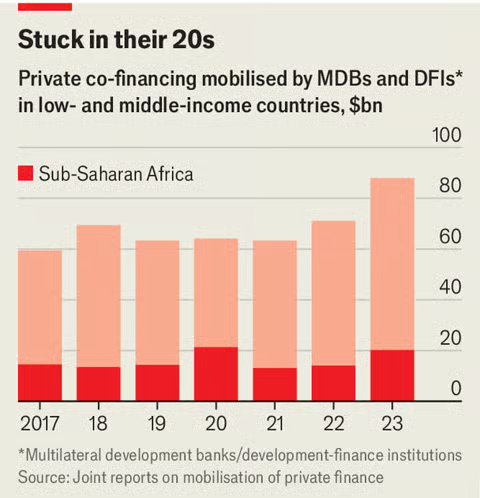

Start with projects backed by multilateral development banks or bilateral financiers. They hoped to attract co-financing from private partners by shouldering some of the risks. For example, they might offer cheap funding to get a project off the ground or a guarantee in case it fails. By their own reckoning they mobilised $88bn of private finance for low- and middle-income countries in 2023, only a belated jump after years of stagnation (see chart). Just $20bn went to sub-Saharan Africa, of which $10bn reached the poorest countries. By comparison, the region received $62bn of aid that year.

In 2018 a task-force launched at Davos, the annual gathering of the World Economic Forum, envisaged that every public dollar could whip up two or more from the private sector. Such ratios are rarely achieved. A forthcoming study by odi Global, a think-tank in London, examines a subset of investments called “blended concessional finance”, where some of the capital comes at below-market rates. It finds that by 2021 each dollar was attracting about 59 cents of private co-financing in sub-Saharan Africa, and 70 cents elsewhere. Besides, too narrow a focus on ratios can distort priorities. The simplest way to bring in private capital is to pick easy projects in safe countries. But development finance is most needed where investors least want to go.

Many of those places are in sub-Saharan Africa. Less foreign investment trickles into the region now than it did when the phrase “billions to trillions” was coined. Private investment in infrastructure projects has also tumbled. The financial flows between African governments and their private creditors have reversed: since 2020, banks and bondholders have received $36bn more in repayments and interest than they have given out in new credit. Capital swilled out of the continent as interest rates rose elsewhere.

The World Bank’s president, Ajay Banga, has acknowledged that the language of “billions to trillions” was “unrealistic” and “bred complacency”. Its chief economist, Indermit Gill, has called the vision “a fantasy”. That is a change of tone, not of heart. The bank has asked a team of business executives to identify barriers to investment. It is experimenting with new models where loans are bundled up and sold on to private investors, rather than sitting on its books as they do now. The African Development Bank, another multilateral lender, has pioneered similar ideas.

It’s still all about the money

The last decade offers some lessons. Mr Valahu thinks the mistake was to assume that institutional investors in rich countries were queuing up to buy infrastructure assets in Africa, while overlooking local pools of capital such as Nigerian pension funds. Mr Sembene argues that investors stay away because they overestimate risks. The evidence on that front is mixed. Over the past three decades private companies in sub-Saharan Africa were more likely than those in other places to default on development-finance loans—but when they did, more of the outstanding debt was eventually recovered.

Meanwhile, investors complain there is nowhere to put their money. The un reckons an annual $4trn more is needed to reach sustainable development goals. But there is not a queue of oven-ready projects. Four-fifths of African infrastructure schemes fail at the feasibility or business-plan stage. “How do we intervene early to get projects to bankability?” asks Tshepidi Moremong of Africa50, a fund set up by African governments, to help with technical studies and financial structuring.

But wooing private money can backfire. Governments get themselves into tangles when trying to assure investors of revenues. Under offtake agreements with private energy firms, Ghana has handed over hundreds of millions of dollars for power it does not use. It also loses money by selling electricity to consumers at less than it costs to buy. The problem is a general one: in countries with a lot of poor people, it is hard to run utilities profitably while also making them affordable.

An “ideological faith” in market-based approaches has blinded policymakers to their shortcomings, argues James Leigland, who used to work on public-private partnerships in Africa for the World Bank. About 95% of infrastructure spending on the continent comes from the public purse, he notes. Why not try to use that money more efficiently, rather than tilting at privately financed windmills?

The standard response is to gesture at the scale of the challenge. Only 17% of sdg targets are on track to be met by their original end date of 2030. Many delegates in Seville will argue that Africa needs more of both kinds of finance, public and private. Right now, it is getting little of either.