Blog

Beyond the Money: How IFIs and MDBs Can Better Support Pandemic Recovery in Africa ?

The case for boosting the lending capacity of international financial and development institutions has already been persuasively made. Expectations of progress on this front are firming up, fueled by the multilateralist stance signaled by the incoming US administration. However, optimizing the support of multilateral institutions for resilient economic recovery in low-income countries (LICs) will require more than loosening the purse strings. More than ever, multilaterals must figure out how to use their scarce resources more effectively. While these institutions have been down this road before, they have not always fully delivered. Based on a few stylized facts, I propose some critical steps—many of which are long overdue—that international financial institutions (IFIs) and multilateral development banks (MDBs) must take if their money is to work more effectively to support African countries recover from the pandemic’s fallout.

Get the financing numbers right and walk the talk

On April 17, 2020, the World Bank and the IMF convened a meeting with African leaders, bilateral partners, and heads of other regional and multilateral institutions to galvanize support for COVID-19 response in the continent. Key private sector representatives were either silent or absent. Still, the press release issued at the end of the meeting estimated private creditor support would be around $13 billion in 2020, narrowing the financing gap significantly to an estimated $44 billion. Ultimately, private sector participation in the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) was lacking, significantly limiting the range of financing options available to African countries.

While exploring ways to support economic recovery in African LICs and beyond, IFIs and MDBs would be well-advised to draw lessons from the DSSI experience. They will need to make financing assumptions more realistic this time around. And a sensible way to minimize risks of estimation errors is to enable all stakeholders—both public and private—to speak for themselves and make their voice and concerns heard and their needs known. More generally, inclusive collaborative approaches remain critical for an international financial system that leaves no partner behind.

In Africa, experience shows that estimates of financing needs for crisis resolution have often widely differed according to national, regional, and multilateral sources, adding confusion about the actual needs. The costing of pandemic recovery is not likely to be an exception. Efforts by multilaterals to help harmonize costing figures, in collaboration with national and regional authorities, will therefore be a useful endeavor with high potential payoff. While the IMF is expected to play an important role given its comparative advantage and recent mandatefrom the G20, African governments and regional institutions must also actively play their part. When capacity weaknesses threaten their ability to do so, multilaterals must stand ready to help with technical assistance.

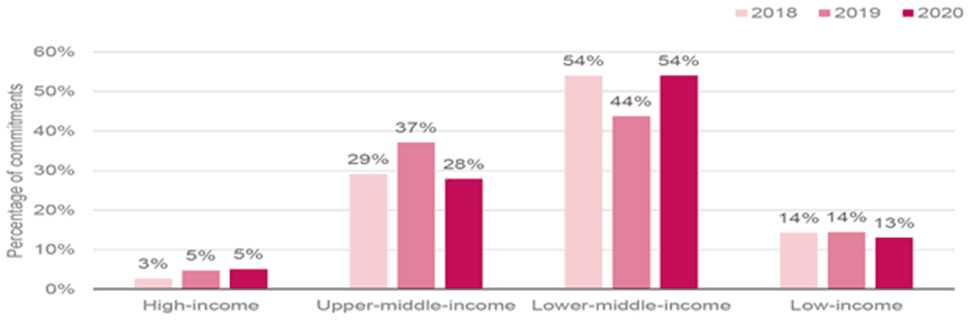

Recent patterns of ODA allocations among major donors have disproportionately favored middle-income countries over LICs. While overall commitments from IFIs and other multilateral institutions have substantially increased this year compared to 2019, the proportion of IFI commitments to LICs have actually declined during the same period, down to only 13 percent. In addition, actual disbursements by a number of multilaterals have failed to keep up with commitments made to LICs. At the same meeting, the World Bank reiterated its pledge to provide up to $160 billion in financial support, including $55 billion for Africa, over the next 15 months to “help countries protect the poor and vulnerable, support businesses, and bolster economic recovery.” But recent research by my colleagues at CGD suggests that the institution has only disbursed $21 billion, and is on track to miss the actual target for IDA and IBRD lending by $25 billion.

More generally, multilaterals must rise to the challenge posed by the worst shock in generations, which LICs are currently coping with. By miscommunicating their commitments, multilaterals are poised to hurt LICs by misguiding national policymakers and development partners into underestimating actual financing needs. A good communication strategy on the part of multilateral lenders must be, therefore, a key element of their support package for pandemic recovery.

Think and act outside the box

For effective contribution to pandemic recovery in Africa, MDBs and IFIs will need to break free from the business-as-usual mentality. This requires a greater sense of innovation along with a nimble response to changing culture and needs in member countries. There are three areas

where I believe innovative solutions and actions—as well as a clean break from past practices—are much needed:

1. Debt crisis prevention and resolution

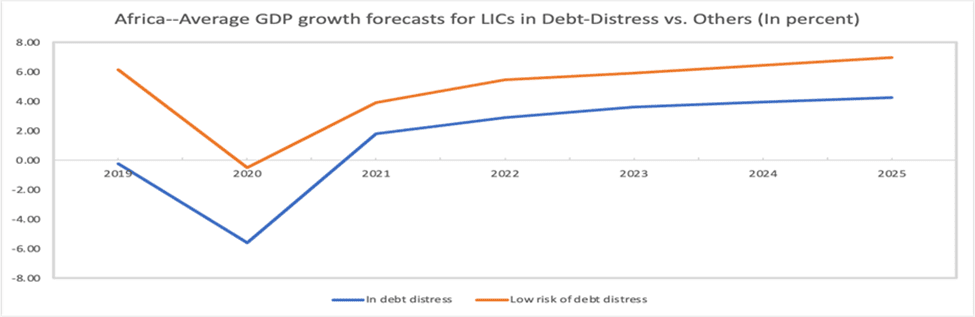

The pandemic crisis is taking a heavy toll on debt-distressed countries in Africa. Not only have these countries registered zero growth heading to this pandemic year, but they have also been hit harder by the crisis and will recover more slowly than their peers assessed to be in low risk of debt distress.

Figure 2. Comparison of economic outlook for African LICs according to debt situation

Source: IMF and author’s calculations.

Note: Countries selected based on the IMF-World Bank Debt Sustainability Framework, which classifies six African countries as being in debt distress as of November 2020: the Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Principe, Somalia, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. Zambia is added to the list in light of recent developments. Countries assessed to be in low risk of debt distress are Madagascar, Tanzania, and Uganda.

Against this background, there is ample scope for IFIs and MDBs to help avert a potential debt crisis in a growing number of LICs, notably by developing innovative ways to help facilitate debt restructuring and avoid new episodes of debt distress. Concrete actions expected from MDBs and IFIs include:

- reassessing their crisis prevention and resolution toolkits to fill potential gaps;

- improving the reliability and effectiveness of existing frameworks for gauging debt sustainability in LICs, particularly IMF-World Bank Debt Sustainability Analyses;

- supporting the design of new legislation that enables orderly sovereign debt workouts;

- addressing the current deficiencies of the broken system of sovereign debt restructuring applicable to LICs; and

- promoting debt transparency from both debtors and creditors.

2. Country platforms

Multilateral support for LICs’ pandemic recovery plans must hinge on a thorough assessment of their sustainability. In turn, this implies due consideration of the soundness of the policy and reform packages that underpin these plans. In addition to the IMF’s work in this area, multilaterals still use a variety of other assessment tools, resulting in an unproductive proliferation of institution-specific conditions and targets set for LICs to meet. Multilateral institutions should agree on a collaborative approach to supporting and assessing recovery plans. To this end, the time is long overdue for concrete steps to materialize the recommendation of the G20 Eminent Persons Group to enhance the impact of development policies and financing by “governing the system as a system rather than as individual institutions.”

The renewed interest in country platforms from the Italian chair of the G20 is a hopeful sign. My colleague Mark Plant suggests in previous work that satisfactory progress on this front will require answers to hard questions, including about their purpose, inclusiveness, appropriate M&E framework, and the respective role of involved stakeholders. In the current context, quick recovery is clearly a strong objective any platform could legitimately seek to achieve. And for more effective support to recovery efforts, MDBs and IFIs need to coalesce around select domestic and regional policy initiatives and programs with demonstrated growth potential. At the same time, helping make the recovery inclusive should rank high on the agenda, as this was a key shortcoming of the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper initiative in sub-Saharan Africa.

There is a need for country platforms to help find effective solutions to the free-rider problem that is typically associated with the execution of global development initiatives. The implementation of the G20’s Compact with Africa is illustrative, as the strength of the commitment to the initiative was perceived in its early stages to be uneven across the IMF, the World Bank, and the African Development Bank. While implementing investment promotion initiatives in which they team up with multilaterals and other development partners, many LIC officials have also expressed frustration about being among the few sides—if not the only—expected to make binding and actionable commitments. Under any new country partnership, it is, therefore, critical to ensure that each participating stakeholder commits to specific, concrete, and time-bound actions to help achieve set goals.

3. Private finance

In July 2015, as part of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, leaders from 193 UN member states encouraged MDBs to “further develop instruments to channel the resources of long-term investors towards sustainable development.” In response, various initiatives have since been taken. In 2017, MDBs and DFIs targeted a 25-35 percent increase in the mobilization and catalyzation of private capital over three years, in line with the Hamburg Principles adopted by the G20. More recently, several MDBs adopted the common “value for money” framework, which is an innovative solution aimed at optimizing the use of available concessional and nonconcessional resources.

The thinking and rhetoric have evolved in recent years, but must be meet with actions if multilaterals’ strong potential to help boost private investment are to be fulfilled. While it is still early to predict the outcome of these initiatives, a number of missteps give little reasons to be optimistic about their capacity to support efficiently pandemic recovery plans by mobilizing sustainable private finance at decisive levels. A joint collaborative framework among key multilaterals to achieve this goal is still lacking. In addition, no meaningful consultative process on a broad scale has thus far been undertaken to bring onboard private sector stakeholders from aid-recipient countries.

LICs and their multilateral partners must take more decisive steps, including overcoming regulatory impediments to deeper and more inclusive domestic financial sector and catalyzing private investment through innovative instruments such as diaspora and green bonds. Critically, they should join efforts to implement an ambitious reform agenda that addresses both the demand and supply sides of corruption which remains a serious impediment to private sector development and economic growth.

Moving forward with responses that match circumstances

Clearly, strong and resilient pandemic recovery in African LICs will need to build on the leading engagement of their own governments. But it also hinges on multilaterals’ effective support, with their financing and advisory solutions being tailored to country- and region-specific circumstances. Ultimately, success will require greater accountability, bold leadership, and a genuine reform drive from both African governments and their multilateral partners.

African LICs may be caught in the same pandemic storm, but they are not all in the same boat.