Blog

Fixing Africa’s debt challenge

Africa’s economic growth over the last decade has coincided with a rapid accumulation of external debt. Many nations have taken advantage of a flurry of low-cost international credit for budgetary and balance-of-payment supports, targeted mainly to accelerate development plans.

Today, the total amount of external debt owed to foreign lenders has surpassed the $1 trillion mark, and annual servicing costs have broken the $100 billion threshold. Resolving the debt challenge is thus crucial for the continent’s future progress.

Just like a duck is to water, sovereign economies worldwide all borrow now and then for various reasons. What turns this relationship into a red herring is when the value of debt owed surpasses by a large percentage how much the nation produces to pay the debt – debt to GDP ratio. Despite the rapid increase in debt levels since 2011, Africa’s median external debt to GDP ratio was still relatively low at 41% at the end of 2021. Roughly two-thirds of all African countries had an external debt-to-GDP ratio of below 50%, while ten countries had external debts that exceeded 75% of their national GDP for that year.

These countries, including Cabo Verde, Djibouti, Angola, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sudan, Tunisia, and Zambia, are classified – according to the IMF – as “critically indebted.” In 2021, Zambia became the first African country to default on its debt.

If urgent efforts are not taken, many nations may follow this path.

Historical origin of debt relief

The movement to rethink Africa’s debt goes back many years to the oil shocks of the 1970s. At a time when many nations were suffering economic stagnation as oil prices collapsed and debt levels soared, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) offered financing solutions that included high-interest loans, privatization of state corporations, and slashing of state subsidies.

Slow economic growth and rampant corruption at the time meant that many nations could not repay the debt within stipulated schedules and, therefore, returned to the borrowing market for more debt for budgetary support. In 1996, the World Bank and IMF designed the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative (HIPC) to eliminate $100 billion of the debt owed by the poorest countries to multilateral lenders. The plan was to reduce the debt of Global South countries to sustainable levels – defined as no more than 150% of the value of annual export revenues.

At the same time, a growing movement of civil society groups under the African Social Forum (ASF) began calling for full multilateral debt cancellations, urging creditor nations to drop conditions that accompanied debt relief packages such as privatization and trade liberalization, because “these have devastated our economies long enough.”

The movement received a shot in the arm in 2004, when after the United States and its allies invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime, the oil-producing nation had almost 95% of its sovereign debt canceled. Then Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, who held the chairmanship of the G-8 said, “There’s a growing consensus that the next step is [to provide] up to 100% debt relief.”

At a G-8 finance ministers meeting in February of the following year, the world’s richest nations agreed in principle to cancel up to 100% of the debts of the poorest countries. Mr. Brown proposed that rich countries put up money to pay off the debts of African countries to the World Bank and IMF and that the vast gold reserves held by the IMF be sold to finance debt relief.

None of those ideas came to fruition.

Debt relief is critical

As public debt reached new levels, there was brief hope during the pandemic that wealthy nations could finally keep their promises to offer debt relief. The G20 set up the Paris Club Debt Service Suspension Initiative to offer temporary debt moratoriums to the least developed countries, recognizing the toll the COVID-19 pandemic had inflicted on their economies. As part of the plan, 48 out of 73 eligible countries participated in the initiative before it expired at the end of December 2021. From May 2020 to December 2021, the initiative suspended $12.9 billion in debt-service payments owed by participating countries to their creditors.

While the initiative partially alleviated the situation, it left African countries classified as middle-income economies in limbo, since they were barred from participating. The consequences, as expected, were severe. Zambia soon defaulted on its debt. Ghana has also been in default since the end of 2022 and was rescued recently by a multi-billion dollar bailout from the IMF. Meanwhile, Kenya’s credit rating was downgraded by major rating agencies in May, citing sovereign liquidity risks.

Obstacles to debt relief

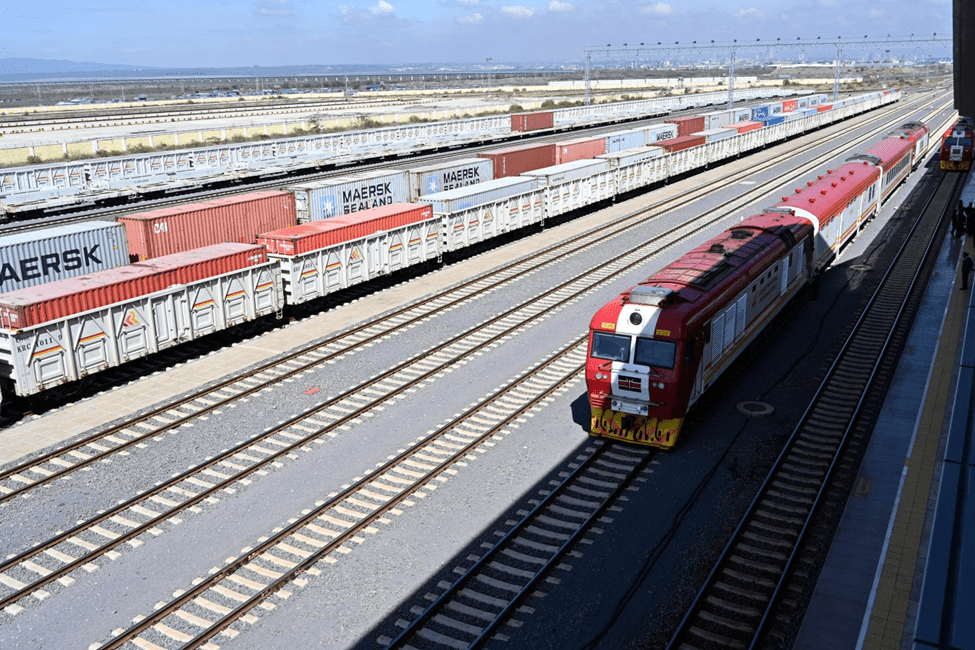

Debt relief will not be a walk in the park since the continent owes many different lenders. China is one of them. The world’s second-largest economy stepped in to offer bilateral development finance for Africa, building mega infrastructure projects from railways in Ethiopia and Kenya to seaports in Nigeria and Tanzania. However, its financial packages come in the form of loans that must be repaid within stipulated timelines. According to the China Africa Research Initiative at John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Chinese loan commitments make up around 12% of the continent’s total external debt, making it the single largest bilateral donor.

In the case of Zambia, China – its largest lender – slugged efforts to cancel its debt. But China on its part declines to bear overwhelming responsibility for the continent’s debt crisis and has called on multilateral development banks to participate in debt relief, which they reject.

This back-and-forth blame game makes it even harder for any concrete measures to be implemented, even as the public debt levels keep soaring.

Alternative solutions?

Should debt restructuring efforts prove impossible, African nations have another ace up their sleeves. They could push for debt rescheduling to extend the repayment period or adjust the terms of existing loans. This would allow countries to reduce their debt service obligations in the short term, providing breathing space for economic recovery post-pandemic and the effects of the Ukraine war. If rescheduling doesn’t work, they could demand debt-for-development swaps to convert a portion of their debt into investments in development projects or social sectors.

Some Asian countries like Sri Lanka are considering this approach, which would allow debt payments to be redirected towards priority areas such as education, healthcare, or infrastructure developments. However, debt-for-development swaps would have to be facilitated by multilateral institutions or bilateral agreements, tying up the continent, possibly, in another round of SAPs or dead aid cycles.

Solving the debt challenge will not alleviate Africa’s economic problems or reignite the fight against poverty. But a concerted effort combining debt relief and other auxiliary measures could go a long way in assisting countries to direct more of their budgetary allocations to priority sectors such as education and healthcare.

Citations

Stein, Howard, and Machiko Nissanke. Structural Adjustment and the African Crisis: A Theoretical Appraisal.” Eastern Economic Journal 25, no. 4 (1999): 399–420. Retrieved June 3, 2023, from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40325948

UN digital magazine. New urgency for cancelling Africa’s debt (April 2005). UN. Retrieved June 3, 2023, from https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2005/new-urgency-cancelling-africa%E2%80%99s-debt

Sami Abdullahi, Rusmawati Said, Normaz Wana Ismail, and Nur Syazwani Mazlan. Public debt, institutional quality and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Institutions and Economies (2019): 39-64.

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Towards sovereign debt restructuring in Africa: comments and recommendations (2022). ECA Policy Brief No. ECA/22/026. Retrieved June 3, 2023, from https://repository.uneca.org/handle/10855/49310